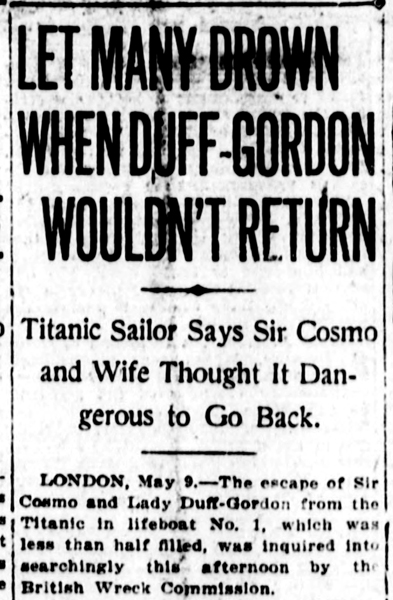

My post of April 10, The mystery of the Money Boat, told how Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife, Lady Lucy, escaped the sinking Titanic in lifeboat 1.

My post of April 10, The mystery of the Money Boat, told how Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife, Lady Lucy, escaped the sinking Titanic in lifeboat 1.

Since then, you may have seen Julian Fellowes’ version of what happened on Boat 1 as the ship actually went down, in the final part of his increasingly muddled and disappointing Titanic TV series.

I’ll now take up the story once more. The day after the tragedy, when all the survivors were safely aboard the rescue ship Carpathia, Sir Cosmo wrote each of the sailors and firemen who had been aboard Boat 1 a cheque for £5, and they all posed together for a photograph.

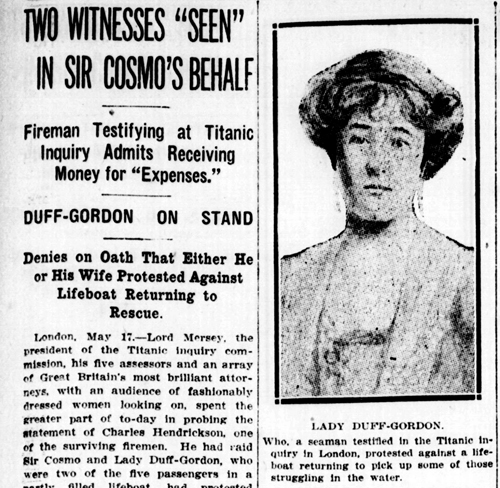

When that photo was subsequently published in the world’s press, its incongruous smiling faces seemed to suggest the Duff Gordons’ callous indifference to the tragedy. Lady Duff Gordon nonetheless insisted that Sir Cosmo had simply made a generous gesture to men who were in financial difficulties, and that the real mystery was why other survivors had not done the same.

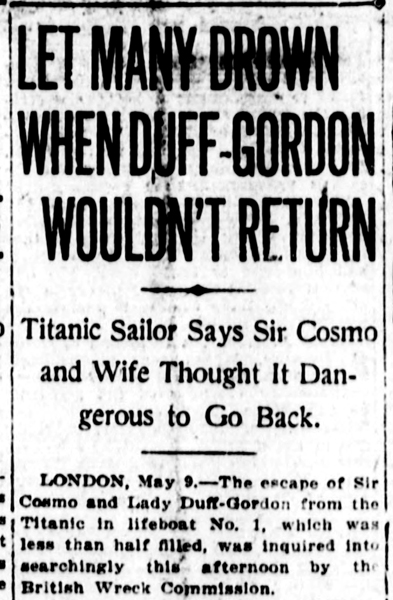

The World, New York, May 9 1912

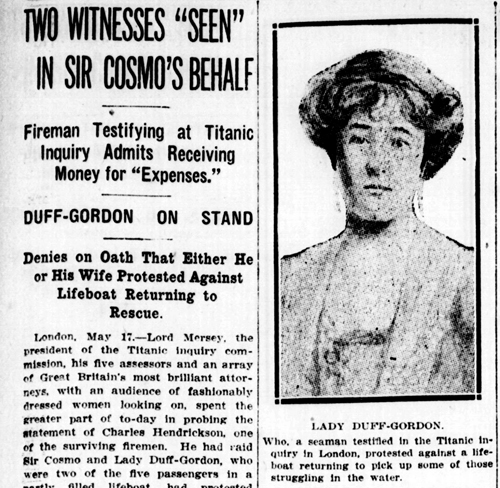

At the British inquiry, none of those aboard Boat 1 pretended that they had made the slightest effort to help their fellow passengers. Their evasive testimony left the impression that as the Titanic was going down, they had simply rowed away. Lady Duff Gordon said she was too seasick to know what was going on; Sir Cosmo, that he was too concerned about his wife to notice. Fireman Charles Hendrickson, on the other hand, said he had wanted to go back, but the Duff Gordons had begged the crew not to do so.

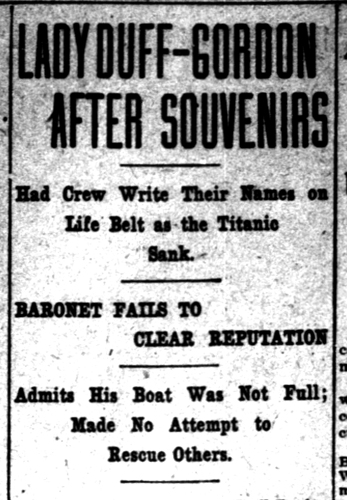

Lookout George Symons insisted “I never heard anybody of any description, passengers or crew, say anything as regards going back” – in fact he claimed that he had heard nobody say anything at all, for the entire five hours they were in the boat. Referring repeatedly to himself as the “master of the situation”, he argued that “I used my own discretion”, fearing that desperate swimmers might swamp the boat and drown them all.

Under cross-examination, however, Symons admitted that a “gentleman” acting on behalf of the Duff Gordons had come to his home the previous weekend. Talking him through his impending evidence, the “gentleman” had invited him to agree with a number of statements that included the phrases “master of the situation” and “used my discretion”.

The Attorney General summed up Symons’ testimony in damning terms: “Your story is; the vessel had gone down; there were the people in the water shrieking for help; you were in the boat with plenty of room; nobody ever mentioned going back; nobody ever said a word about it; you just simply lay on your oars. Is that the story you want my Lord to believe?” Symons replied: “Yes, that is the story”.

New York Tribune, May 18 1912

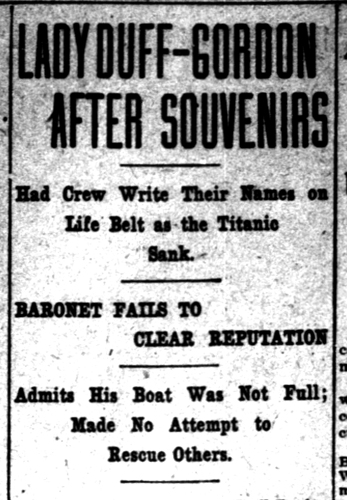

Sir Cosmo himself, confronted on his failure to help the mass of drowning victims, blustered and flailed: “It is difficult to say what occurred to me… I was minding my wife, and we were rather in an abnormal condition, you know. There were many things to think about, but of course it quite well occurred to one that people in the water could be saved by a boat, yes.” At one point, he expostulated: “We had had rather a serious evening, you know.”

Asked, “Was not this rather an exceptional time, 20 minutes after the Titanic sank, to make suggestions about giving away £5 notes?”, Sir Cosmo replied, “No, I think not. I think it was a most natural time.” Another lawyer pursued the issue: “Why do you suggest that it was more natural to think of offering men £5 to replace their kit than to think of those screaming people who were drowning?” “I do not suggest anything of the sort”, responded Sir Cosmo.

The inquiry concluded that: “The very gross charge against Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon that, having got into No.1 boat he bribed the men in it to row away from the drowning people is unfounded … The members of the crew… might have made some attempt to save the people in the water, and such an attempt would probably have been successful; but I do not believe that the men were deterred… by any act of Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon’s. At the same time I think that if he had encouraged to the men to return to the position where the Titanic had foundered they would probably have made an effort to do so and could have saved some lives.”

While Sir Cosmo was cleared of the worst allegations, the inquiry’s verdict upon his character was hardly complimentary. An extraordinary array of society figures and minor royalty, including the wife of prime minister Herbert Asquith, had queued to watch his public humiliation. Although Sir Cosmo was to live another twenty years, according to his wife “he never lived down the shame”.

The Washington Herald, May 19 1912

All text © Greg Ward, and adapted from the Rough Guide to the Titanic. Some of this post also appeared in an article I wrote for msnbc.com.

Back in April, I had a friendly email from David Bibb, who was reading my Rough Guide to the Titanic. He took issue with my comment in the introduction that “the evidence suggests that [the Titanic disaster] faded from prominence with the coming of the Great War”.

Back in April, I had a friendly email from David Bibb, who was reading my Rough Guide to the Titanic. He took issue with my comment in the introduction that “the evidence suggests that [the Titanic disaster] faded from prominence with the coming of the Great War”. I’ve been in Las Vegas this week, which gave me the chance on Wednesday to re-visit the

I’ve been in Las Vegas this week, which gave me the chance on Wednesday to re-visit the  For me, after being so caught up with the Titanic story for the last couple of years, it was a profoundly moving experience to come face to face with the centrepiece of the exhibition, the so-called Big Piece of the Titanic herself.

For me, after being so caught up with the Titanic story for the last couple of years, it was a profoundly moving experience to come face to face with the centrepiece of the exhibition, the so-called Big Piece of the Titanic herself.

My post of April 10,

My post of April 10,