Has there ever been a front page to match this one?

Has there ever been a front page to match this one?

This is the New-York Tribune from April 19, 1912. In the four days since the Titanic hit the iceberg, the world has had no news of the tragedy beyond a piecemeal list of the victims.

Now the rescue ship Carpathia has finally reached New York, carrying the only survivors of the tragedy, and at last the newspapers have the “THRILLING DETAILS” to get their teeth into.

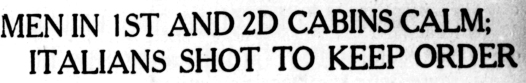

Or do they? A quick look at the headlines below, all clipped from this same page, reveals that while the stories are certainly thrilling, it’s quite possible that none of them is actually true.

The stories here include such persistent myths as that Captain Smith shot himself, that White Star Line president J. Bruce Ismay escaped with a hand-picked crew, and that an officer shot panicking “Italians”.

A century later, we still don’t know whether any of these things really happened.

Here’s the second selection from my top ten Titanic songs – Down WIth The Old Canoe, recorded by the Dixon Brothers in 1938. Listen to it by clicking on the image below.

Here’s the second selection from my top ten Titanic songs – Down WIth The Old Canoe, recorded by the Dixon Brothers in 1938. Listen to it by clicking on the image below.